Authors: Julia van Huizen, Edward Jansen en Noortje Mentink

Amsterdam Data Collective has conducted research into the impact of climate risks on Dutch real estate. In this article they want to answer the following question: what is the impact of climate risks on house prices in the Netherlands? To that end, they discuss the implications of the findings from both the perspective of homeowners and that of financial institutions. The research was done with data on real estate transactions provided by the location-driven data company Matrixian.

What is climate risk?

In 2007, the Interngovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) [1] concluded that the significant increase in greenhouse gases worldwide since 1750 has been caused by human activities. Recently, the IPPC stated that human-induced climate change around the world is increasingly impacting weather and climate extremes such as heat waves, heavy precipitation, droughts and tropical cyclones [2]. Such climate extremes result in climate risks, which affect the global population, including through exposures from the financial sector. With regard to the latter, it is customary to divide climate risks into two subcategories: physical risks and transition risks.

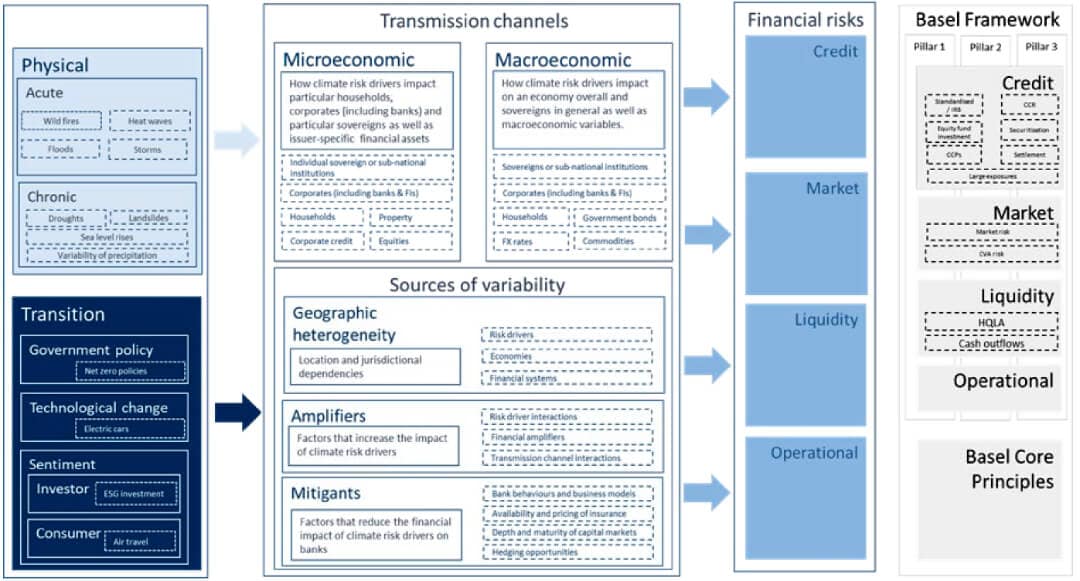

Source: “Climate related risk drivers and their transmission channels”, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Retrieved from: Climate related risk drivers and their transmission channels on 15/09/2022.

Flood risk is the most relevant physical risk for the Dutch real estate sector

The physical effects resulting from climate change that negatively affect the population and the economy are called physical risks. Extreme weather events such as heat waves, wildfires, storms and floods are all examples of physical risks.

The presence of physical risks leads to financial risks through so-called transmission channels. These are the mechanisms through which physical risks can have an impact on both microeconomic and macroeconomic factors. De Nederlandsche Bank [3] has identified flood risk as one of the most relevant risks for the Dutch financial sector; for the real estate sector in particular, de Nederlandsche Bank [4] notes that the size of domestic real estate positions that are vulnerable to flooding, together with the lack of explicit inclusion of physical risk in real estate valuations, is very problematic.

Transition risk is difficult to control and mitigate

Transition risk can be defined as the risk that arises in the process of (abruptly) switching to a circular low-carbon economy. Drivers of these risks include changes in public sector policies, laws and regulations, technology and sentiment among investors and other market participants. Since many of these drivers are uncertain and difficult to predict, it can be a challenge to get a good grip on what transition risks homeowners and banks will face, even in the near future. It is therefore not surprising that the lack of explicit inclusion of transition risks in property valuations is also mentioned by De Nederlandse Bank [3] as a point of concern.

Why is it important to integrate climate risks into the real estate sector?

In order to mitigate financial risks, climate-related financial risks must be included in the financial system in a timely manner. For the real estate sector, this could mean that these risks have to be integrated into real estate valuations. For this study, the incorporation of two types of risks was examined: flood risk as a driver of physical risk and the energy labels of houses as a driver of transition risk.

A flood can lead to uninsured losses for homeowners and banks

For both homeowners and financial institutions it is important that the flood risk is included in the valuations of real estate. For homeowners, a potential flood can damage their homes leading to uninsured losses. For financial institutions that provide mortgages, a flood can lead to financial risks in two ways. First, borrowers’ ability to repay can be compromised. Second, banks may not be able to fully recover the value of damaged collateral, increasing the portfolio’s Loss Given Default (LGD). These effects will therefore lead to larger credit losses.

Mandatory energy efficiency can lead to a fall in real estate prices

Similar to the case of flood risk, both homeowners and financial institutions benefit from accurate processing of transition risk in real estate valuation. A gradual transition is preferred from both perspectives, as this will allow the economy and financial markets to adapt and avoid losses due to tightened sustainability requirements. In the case of energy efficiency, if owners of residential and commercial buildings have to invest abruptly to meet sustainability requirements, they can come under pressure with regard to their repayment obligations on the relevant loans. Furthermore, problems can arise when selling or renting a building due to changing sustainability requirements, reducing the value of unsustainable buildings. In order to enable a gradual transition, the Dutch government decided years ago that office buildings must have at least an energy label with a C value by 2023. If an office building does not comply with this, its use is prohibited. Therefore, owners of office buildings with a D to G value must improve the energy efficiency of the building in time to meet this obligation. In addition, the government’s sustainability plans for rental homes aim to make an energy label with a C value mandatory by 2030. These developments show that the transition is already in progress.

What impact can be observed on the Dutch real estate market?

Modelling

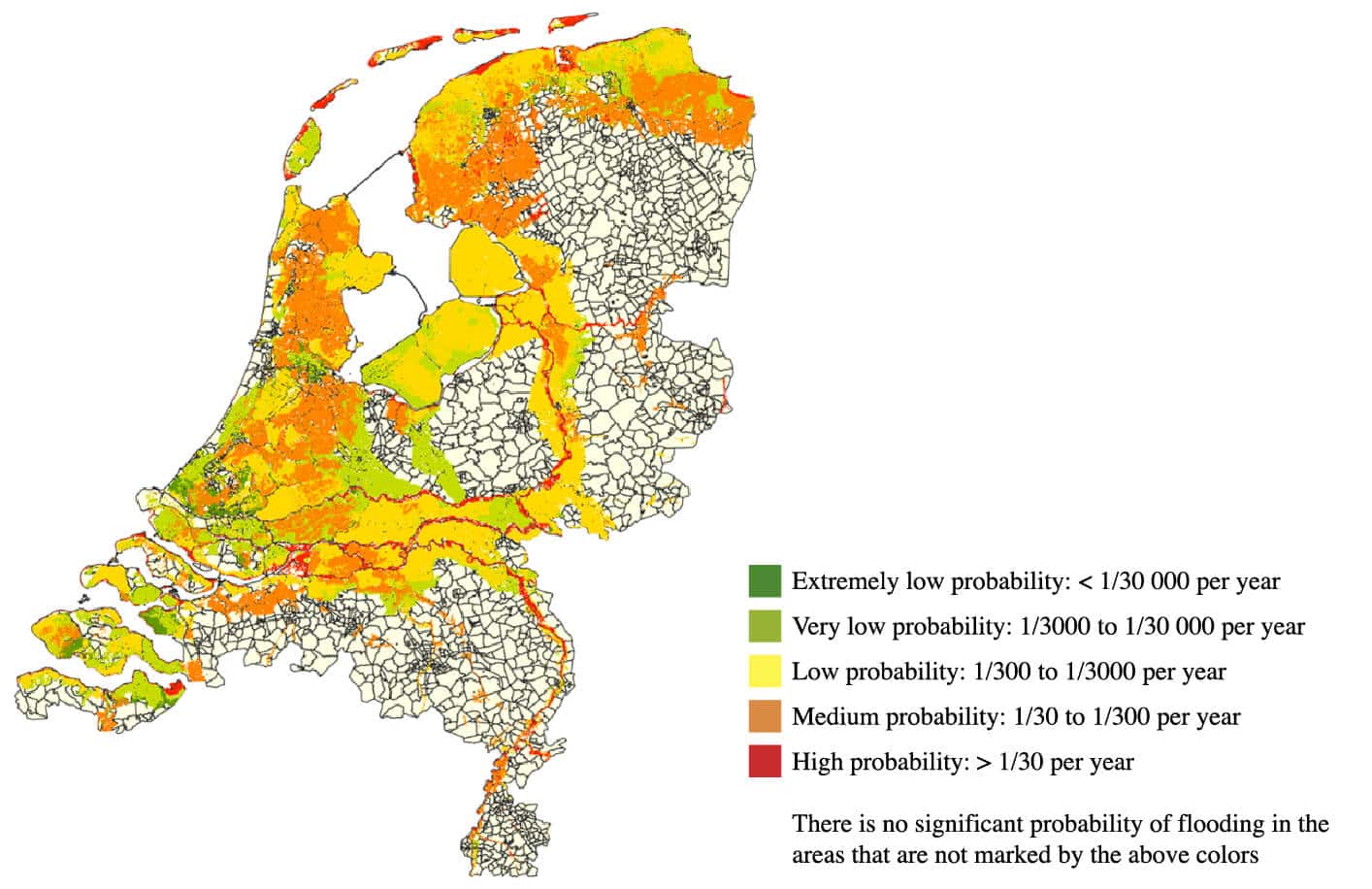

To shed light on the effect of climate risks on house prices, a regression analysis was used to estimate the effect of a set of explanatory variables on the average transaction price per m2 at 4-digit postcode level within the Netherlands over the period 2016-2020. The set of explanatory variables contains as many different relevant factors as the data allows, such as characteristics of houses and residents, and macroeconomic factors. To determine the influence of flood risk and energy efficiency on real estate prices, two variables representing these effects are added to the regression. For the flood risk, specific maps from Climate Impact Atlas about the location-specific flood probability for different flood depths were used. These maps indicate the risk of a certain flood depth if the primary flood defenses meet the 2050 protection standards of the Water Act. For energy efficiency, the share of green energy labels of houses in a postal code was used as a measure. Energy labels with a C value or higher are considered green.

A hedonic approach was used to model house prices, treating climate risks as the sum of the monetary contributions of different attributes. In this way, the influence of each characteristic, including flood risk and energy efficiency, can be estimated at the price. The theoretical model used can be described as a sequential dynamic Hausman-Taylor model, using the Arellano-Bover/Blundell-Bond GMM estimator. This method makes it possible to model dynamic relationships while estimating consistent time-invariant regressors at the same time

Because these data at the 4-digit postcode level have been collected over several years and are readily available, it is possible to model house prices for these 4-digit postcode areas for a range of time points (longitudinal regression). This makes it possible to disentangle much more information than with modeling at one point in time (transverse regression). With this approach, the time-constant individual-specific effect that characterizes a 4-digit postcode area can be separated from other time-varying attributes. By including dynamics in the model, house prices can be modeled as an autoregressive process, which means that the model also takes into account the house prices of the previous year. These are valuable inputs.

Map: The probability of a flood depth of more than 0 cm in one year according to Klimaateffectatlas

Legend: The risk levels as defined by Klimaateffectatlas

Results

Based on data observed at 4-digit postcode level over the years 2016 to 2020, the effect of different flood depths (0cm, 20cm, 50cm and 200cm) on house prices was estimated. All other factors were kept constant and compared to 4-digit postcode areas with no significant flood risk. This led to the following insights:

- average house prices per m2 are lower in areas where the risk of flooding is high.

- average house prices per m2 are higher in areas where the risk of flooding is very low to moderate.

- for a flood depth of 200cm, the effect of a high risk is estimated to be approximately twice as great as for a different (lower) flood depth

These results suggest that the relationship between flood risk and house prices is not strictly increasing or decreasing, suggesting that flood risks are not consistently priced in the Dutch real estate market from the years 2016 to 2020. Moreover, for the years 2016 to 2020, no significant association was found between the average transaction prices per m2 and the share of green energy labels in a respective postcode. This means that no price premium (or discount) has been set for more energy-efficient real estate.

What are the implications of the findings?

The findings indicate that home buyers only consider potential losses in the areas most at risk of flooding. In very low- to medium-risk regions, house prices tend to be higher than in non-risk regions. This may be explained by people’s preference for living close to water. This is a cause for concern because in the future when climate hazards such as flooding become more apparent, it could lead to a sudden repricing of risk, which in turn could destabilize the financial system.

It is also suspected that the lack of effect of energy efficiency on house prices can be attributed to modeling the average house prices of postcode areas, rather than individual houses, which reduces the granularity of a possible effect.

Next steps: challenges in integrating climate risks into the financial system

The results suggest that flood risks and energy efficiency have not yet been consistently priced into the Dutch real estate market. For potential homeowners, this means that they need to be aware of the possibility that they are paying too much for a home. For banks, this means that their books could be exposed to greater credit risk than they think now, as PD, LGD and credit losses could accumulate in the future. It would therefore be beneficial for individual banks and the entire banking sector to conduct scenario analyzes and stress tests to assess the potential impacts when these risks materialize.

Also, in 2023, the European Banking Authority (EBA) is expected to publish an analysis of the integration of environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors into prudential risk models, which may eventually lead to an adjustment of the current capital requirements by the European Commission.

Would you like to know more?

For more information on how to quantify climate risk, please refer to a previous series of articles on the topic of climate risk.

Or you can reach us via:

info@matrixian.com